The Worst Aviation Related Disaster In Australian History:

USAAF B-24D 42-40682 "Pride of the Cornhuskers"

An artist's impression of "Pride of the Cornhuskers" (click to enlarge)

An artist's impression of "Pride of the Cornhuskers" (click to enlarge)

The preparation and checking of equipment was complete. Transfer from bivouac to the Durand marshalling area had gone off without a hitch. All they simply had to do now was wait .... a pastime which soldiers learned very quickly during army life. Some men dozed in the early dawn whilst others smoked and chatted idly. Being 4.15 in the morning, the convoy would soon mount up and commence the 17 mile journey to Durand Airstrip. Many of the waiting diggers had served in Syria. Most were veterans of the Kokoda Trail; however a sprinkling of reinforcements bolstered their ranks. In the quiet corner of each man’s mind, veteran and reinforcement alike may have pondered the fight which lay ahead. For they were about to be airlifted to Nadzab in preparation for the assault upon Lae; and the Japanese had already proved to be a tough and tenacious foe. It was the first time an entire Australian Division, around 10,000 men were to be airlifted into a war zone. In the history of wartime New Guinea, the 7th of September 1943 would be a day to remember. For the men of the 2/33rd Infantry Battalion AIF, it would be a morning they would struggle to forget.

At the opposite end of 7 Mile Drome - known to most as Jackson’s airfield, the Pratt & Whitney engines of an American bomber turned over in the pre-dawn darkness. Flight Officer Howard J. Wood busily worked through his pre- take off checks. Hailing from Nebraska U.S.A, Wood’s mount was christened “Pride of the Cornhuskers” in honour of his home state. At a cost of $297,627.00 to the U.S. taxpayer , it was a huge responsibility for a young man of 21 years. Not to mention the lives of his ten crew members who went about preparing themselves for today’s mission; an armed reconnaissance flight to Rabaul.

The U.S. 403rd Bombardment Squadron, part of the 43rd Bomb Group – 5th Air Force had converted from B-17s over to B-24’s between May and September of that year. The long ranging Liberators were believed to be more suitable for the distances covered in the south west Pacific theatre. This ‘D’ model Liberator, Serial Number 42-40682 could carry a bomb load of 12 x 500 lb bombs when not fitted with supplementary bomb bay fuel tanks. However on this day, the aircraft would be loaded up with just 4 x 500 pounders .... perhaps this decision unwittingly saved many lives. On a reconnaissance mission such as this and with a reduced bombload, “Pride of the Cornhuskers” could manage the return trip utilising her standard internal tanks with a full fuel capacity of 2,800 gallons. Having logged a total flying time of 628 hours, Wood had already accumulated 420 hours in Liberators. And now that the allies were well and truly on the offensive, this young airman had flown 97 hours in the past three months. His Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Harry J HAWTHORNE described the Flight Officer as an experienced pilot.

Beyond the end of the runway, the ground was relatively flat and clear for a distance of approximately 1000 yards. A low ridge, peppered with trees ran perpendicular to the runway. On the reverse side of this tree line, the ground dropped steadily away to form a small valley through which a creek ambled lazily. The undulating ground then rose gently to form a second ridge, much lower than the first. In fact, this second ridge was later determined to be 25 feet lower than runway elevation. Capable of housing a large number of vehicles, this rise was designated the marshalling area for troop transport vehicles bound for Durand Airstrip. Situated within the 7 Australian Division Marshalling area; this holding point lay approximately half a mile from the eastern end of 7 mile drome. When this site was chosen, nobody could have envisaged that troops mustered in this low lying ground would be in harm’s way. On the next ridge to the Durand marshalling area was Wards marshalling area; with the Jackson marshalling area being furthermost from the airfield. The topography consisted of a series of small hills and re-entrants which could comfortably accommodate the embussing of an AIF battalion. As such there were 18 trucks at the Durand marshalling area containing men from A, C and D companies of the 2/33rd Infantry Battalion. The lead truck for ‘D’ Company (known as Don Company) contained Captain John Boyd Ferguson. A popular officer, he served with this unit in Syria until he was injured. Having recovered from his wounds, this would be his first action against the Japanese. Ferguson sat on the passenger seat in the small, cramped cabin of the 3 ton Chevy with the driver seated to his right.

For the drivers of the 158 General Transport Company it was just another routine day in the heat and dust of Port Moresby. Their passengers had already been delayed by 24 hours as a result of bad weather over the Owen Stanley Range. However today’s conditions looked promising. Fully loaded up with rifle or machine carbine ammunition and grenades, the diggers could expect to be in action within a day or so of landing on the other side of the mountains. Some carried 2” mortars, others stowed spare magazines in their webbing for the Bren guns. As such, they were fully prepared for what lay ahead. Or so they thought. USAAF C-47 aircraft at Durand Airstrip awaited their arrival. Previously known as Waigani, Durand Airfield was named in honour of P-39 pilot Edward D. Durand who went missing in action on April 30, 1942.

At the opposite end of 7 Mile Drome - known to most as Jackson’s airfield, the Pratt & Whitney engines of an American bomber turned over in the pre-dawn darkness. Flight Officer Howard J. Wood busily worked through his pre- take off checks. Hailing from Nebraska U.S.A, Wood’s mount was christened “Pride of the Cornhuskers” in honour of his home state. At a cost of $297,627.00 to the U.S. taxpayer , it was a huge responsibility for a young man of 21 years. Not to mention the lives of his ten crew members who went about preparing themselves for today’s mission; an armed reconnaissance flight to Rabaul.

The U.S. 403rd Bombardment Squadron, part of the 43rd Bomb Group – 5th Air Force had converted from B-17s over to B-24’s between May and September of that year. The long ranging Liberators were believed to be more suitable for the distances covered in the south west Pacific theatre. This ‘D’ model Liberator, Serial Number 42-40682 could carry a bomb load of 12 x 500 lb bombs when not fitted with supplementary bomb bay fuel tanks. However on this day, the aircraft would be loaded up with just 4 x 500 pounders .... perhaps this decision unwittingly saved many lives. On a reconnaissance mission such as this and with a reduced bombload, “Pride of the Cornhuskers” could manage the return trip utilising her standard internal tanks with a full fuel capacity of 2,800 gallons. Having logged a total flying time of 628 hours, Wood had already accumulated 420 hours in Liberators. And now that the allies were well and truly on the offensive, this young airman had flown 97 hours in the past three months. His Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Harry J HAWTHORNE described the Flight Officer as an experienced pilot.

Beyond the end of the runway, the ground was relatively flat and clear for a distance of approximately 1000 yards. A low ridge, peppered with trees ran perpendicular to the runway. On the reverse side of this tree line, the ground dropped steadily away to form a small valley through which a creek ambled lazily. The undulating ground then rose gently to form a second ridge, much lower than the first. In fact, this second ridge was later determined to be 25 feet lower than runway elevation. Capable of housing a large number of vehicles, this rise was designated the marshalling area for troop transport vehicles bound for Durand Airstrip. Situated within the 7 Australian Division Marshalling area; this holding point lay approximately half a mile from the eastern end of 7 mile drome. When this site was chosen, nobody could have envisaged that troops mustered in this low lying ground would be in harm’s way. On the next ridge to the Durand marshalling area was Wards marshalling area; with the Jackson marshalling area being furthermost from the airfield. The topography consisted of a series of small hills and re-entrants which could comfortably accommodate the embussing of an AIF battalion. As such there were 18 trucks at the Durand marshalling area containing men from A, C and D companies of the 2/33rd Infantry Battalion. The lead truck for ‘D’ Company (known as Don Company) contained Captain John Boyd Ferguson. A popular officer, he served with this unit in Syria until he was injured. Having recovered from his wounds, this would be his first action against the Japanese. Ferguson sat on the passenger seat in the small, cramped cabin of the 3 ton Chevy with the driver seated to his right.

For the drivers of the 158 General Transport Company it was just another routine day in the heat and dust of Port Moresby. Their passengers had already been delayed by 24 hours as a result of bad weather over the Owen Stanley Range. However today’s conditions looked promising. Fully loaded up with rifle or machine carbine ammunition and grenades, the diggers could expect to be in action within a day or so of landing on the other side of the mountains. Some carried 2” mortars, others stowed spare magazines in their webbing for the Bren guns. As such, they were fully prepared for what lay ahead. Or so they thought. USAAF C-47 aircraft at Durand Airstrip awaited their arrival. Previously known as Waigani, Durand Airfield was named in honour of P-39 pilot Edward D. Durand who went missing in action on April 30, 1942.

(Click to enlarge)

The official history of the 2/33rd Battalion by Bill Crooks titled “The Footsoldiers” records the reaction to the departure of the first aircraft on that fateful morning. Noting the ‘deep-throated blast’ and roar of aero engines at 4.20am, aircraft lights were seen through the trees on the far ridge. A Liberator passed overhead at an estimated height of 100 feet causing one soldier to remark “Christ! He was close. I hope we don’t stay here too long”. Well away from the Durand marshalling area, Flight Officer Wood lined up on the western end of the southernmost runway. Evidence suggests this southernmost runway was classified as the ‘fighter’ strip. Regardless, it was deemed to be of sufficient length for B-24’s to safely complete their take off run. ‘Pride of the Cornhuskers’ would be the second aircraft to depart this morning. The take off was witnessed by Corporal Angus O’BRIEN of the 3rd Australian Divisional Provost Company at the eastern end of the runway. He gave the following evidence during the official inquiry:- “ On the morning of 7 September 1943, I was on convoy duty. At approximately 0430 hours, convoy was halted at the top end of Jackson’s drome facing the drome. I was at the head of the convoy which consisted of 18 vehicles. I heard the roar of the motors of a plane coming up the strip. I looked down the strip but could not at first see any plane. After a few seconds I noticed a fire which outlined the plane engine coming towards me. The fire appeared to be in the cowling of the engine. I glanced back along the convoy and when I looked again the plane was passing overhead. I noticed that it was a Liberator and that the fire was in an engine on the port side of the plane. I estimate that the height of the plane was approximately 30 feet. The breeze from the plane blew the hats off some of the men in the truck. The convoy started to move off and had travelled about 50 yards when I heard the sound of two almost simultaneous explosions come from the direction of the marshalling area. I looked back and noticed a glow in the sky.”

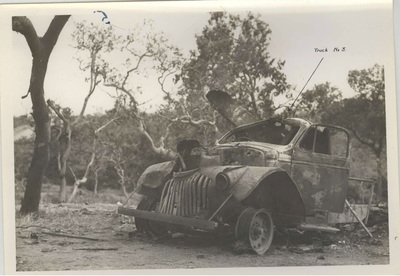

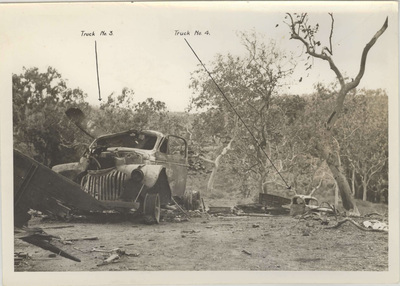

This report of explosions and a ‘glow in the sky’ heralded the worst aviation related disaster in Australian history. For reasons unknown, the Liberator failed to gain sufficient height and hurtled towards the men on the ground. Witnesses yelled of the impending danger but there was no time to take evasive action. The port wing was sheared off when it struck a tree on the downward slope, across the other side of the creek. Like a wounded bird, the huge bomber came crashing down onto the hillside near the Durand marshalling area - spewing forward a wave of burning aviation fuel. Five lorries were hit by flying wreckage and engulfed in the resulting fire which turned night into day. The lorry occupied by Captain Ferguson appeared to take the full shock of the explosion, causing it to overturn. There were no seatbelts fitted to this vehicle. The lorry rolled onto the passenger side and the body weight of the driver undoubtably pinned Captain Ferguson inside the cabin. Both men were incinerated. A three bladed prop from one of the engines spun wildly through the air and slammed into the third lorry in the line of Don Company vehicles. The propeller hub complete with twisted blades, lodged partially on the cabin – coming to rest in the rear tray of the lorry which had been full of men.

© Photos from the 2/33 Australian Infantry Battalion War Diary

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

Neville Edgar LEWIS, a 22 year old Regimental Signaller from H.Q. Company, was on loan to Don Company with two other signallers, Bill ALEXANDER and Alan FURNANCE. He said “I was in the No. 1 truck that Captain Ferguson was in .... there were 21 of us in there. I did not know Captain Ferguson very well as I was normally in H.Q. Company. I was sitting in the back of the truck on a 108 wireless set and just dozing when I heard the noise. I looked out and remember seeing the shape of a plane and then the nose hit the truck and I was flung out and knocked unconscious. I was taken to the hospital and was burned on my legs, arms, back & a head injury. And they took a slice to the second bottom part of my spine. I spent 9 WEEKS in hospital due to my injuries. There was 15 killed out of the 21 in the first truck”.

The small valleys and re-entrants became rivulets of burning aviation fuel. Screams of pain and despair were drowned out by explosions as the flames reached the ammunition in the vehicles. Human torches ran in panic or rolled around on the ground. Veteran Bill Crooks wrote that diggers would suddenly “disappear as either the grenades or 2 inch mortar bombs they were carrying in their clothes or equipment exploded”.

It is evident that two of the 500 lb bombs had exploded immediately following the impact. A third bomb exploded a short time later. The fourth bomb failed to explode and lodged underneath a lorry occupied by men of ‘C’ Company. When Lieutenant Ray Whitfield jumped from the vehicle and tripped over an object, he looked down and saw the tail fins of the 500 pounder lodged behind the front wheels. He said loudly “Christ, please don’t go off”. Ray was the last to leave that vehicle.

The small valleys and re-entrants became rivulets of burning aviation fuel. Screams of pain and despair were drowned out by explosions as the flames reached the ammunition in the vehicles. Human torches ran in panic or rolled around on the ground. Veteran Bill Crooks wrote that diggers would suddenly “disappear as either the grenades or 2 inch mortar bombs they were carrying in their clothes or equipment exploded”.

It is evident that two of the 500 lb bombs had exploded immediately following the impact. A third bomb exploded a short time later. The fourth bomb failed to explode and lodged underneath a lorry occupied by men of ‘C’ Company. When Lieutenant Ray Whitfield jumped from the vehicle and tripped over an object, he looked down and saw the tail fins of the 500 pounder lodged behind the front wheels. He said loudly “Christ, please don’t go off”. Ray was the last to leave that vehicle.

Photo courtesy of: Historical archives of LIFE Magazine

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

The U.S.A.A.F. conducted an investigation into the crash; as did the 7th Australian Division. The official U.S. report considered that factors attributing to the crash were the result of 90% pilot error and 10% weather. Interestingly, the Australian court of inquiry was of the opinion the cause of the crash will always remain a mystery. They indicated there was no evidence of neglect on the part of the pilot. This accident took place in the pre-dawn darkness. Whilst there was a slight mist along the creek line due to the moisture, witnesses on the higher ground near the end of the airfield gave evidence that the weather was clear. In accordance with the darkness before sun rise, Flight Officer WOOD carried out the take-off under instrument conditions. The U.S. report states that he failed to climb to a sufficient altitude before lowering the nose of the aircraft to increase his airspeed. The report goes on to claim, “Going directly from contact to instrument flying in B-24 aircraft, immediately after take-off is trying on the best of pilots, for flight instruments can very easily give erratic readings at the moment the aircraft becomes airborne”. Lieutenant Colonel Harry J. HAWTHORNE, U.S. Army Air Corps stated that under ordinary circumstances, an aircraft should have no difficulty in making the necessary height with the length of runway available. Prior to the aircraft colliding with trees, a number of witnesses (as evidenced by Corporal Angus O’BRIEN) reported seeing flames emitting from a port side engine. Lieutenant Colonel HAWTHORNE made comment regarding this report; indicating that in normal circumstances, flames frequently emerge from the supercharger of an engine. Subsequently he discounted engine failure.

Right or wrong, it has been claimed that a pilot does not really know his aircraft until he has at least 1000 hours in type. With 420 hours in the Liberator, could this horrific accident simply be written off as pilot error? There were rumours at the time, claiming Mexican enlisted men were saboteurs - despite there being absolutely no evidence to support this. This allegation is said to have resulted in service crews entering an unwilling lottery, the loser joining the aircrew on that particular combat mission for which the aircraft was serviced; as a way of discouraging sabotage. If this practice did occur, it was not enforced for very long.

In accordance with the Australian findings, we will never learn the true cause of the accident. Tasked with transporting an entire Australian division and considering the urgency of the time, the 5th Air Force faced a huge work load during late 1943. Japanese strongholds drove the necessity to continue with air strikes against Rabaul and northern New Guinea to ensure success of this current operation. In light of this, it can be said that air force authorities could not, and did not allocate sufficient time and resources into investigating the cause of the crash. Certainly there was not the elaborate Air Crash Investigation and Forensic resources available in 1943, as there is now. However with the luxury of time and sufficient manpower, a more comprehensive conclusion may have been reached in this modern era.

Despite the uncertainty of what caused the accident, what can be proven is the moral fibre of the men who performed their duties during the aftermath of this tragic crash. The courage of the U.S. fire fighters on a rescue mission, clad in asbestos suits that walked directly into the flames is without question. And the bravery of diggers who thought of their mates, before themselves is reflected by a quote from the official 7th Division Inquiry:- “At the time of the crash there was not the slightest degree of panic and everyone who was able to do so, did what they could to assist the injured. Considerable presence of mind and initiative on the part of members present, no doubt contributed largely to minimising injuries and saving lives.” The men received no honours or awards, because despite the fact they awaiting to emplane to fly into battle, they were not already in battle. The strict censorship at the time of the crash also prevented any honours or awards for the heroic actions of these men.

Sixty infantrymen of the 2/33rd Battalion and two drivers of the 158 General Transport Company lost their lives as a result of the crash. The eleven crew in “Pride of the Cornhuskers” also suffered a terrifying death. A total of 73 men died, with over 90 subjected to horrific burns. It is without doubt, Australia’s worst aviation disaster, yet it remains one of the least documented and known incidents of the Second World War.

Right or wrong, it has been claimed that a pilot does not really know his aircraft until he has at least 1000 hours in type. With 420 hours in the Liberator, could this horrific accident simply be written off as pilot error? There were rumours at the time, claiming Mexican enlisted men were saboteurs - despite there being absolutely no evidence to support this. This allegation is said to have resulted in service crews entering an unwilling lottery, the loser joining the aircrew on that particular combat mission for which the aircraft was serviced; as a way of discouraging sabotage. If this practice did occur, it was not enforced for very long.

In accordance with the Australian findings, we will never learn the true cause of the accident. Tasked with transporting an entire Australian division and considering the urgency of the time, the 5th Air Force faced a huge work load during late 1943. Japanese strongholds drove the necessity to continue with air strikes against Rabaul and northern New Guinea to ensure success of this current operation. In light of this, it can be said that air force authorities could not, and did not allocate sufficient time and resources into investigating the cause of the crash. Certainly there was not the elaborate Air Crash Investigation and Forensic resources available in 1943, as there is now. However with the luxury of time and sufficient manpower, a more comprehensive conclusion may have been reached in this modern era.

Despite the uncertainty of what caused the accident, what can be proven is the moral fibre of the men who performed their duties during the aftermath of this tragic crash. The courage of the U.S. fire fighters on a rescue mission, clad in asbestos suits that walked directly into the flames is without question. And the bravery of diggers who thought of their mates, before themselves is reflected by a quote from the official 7th Division Inquiry:- “At the time of the crash there was not the slightest degree of panic and everyone who was able to do so, did what they could to assist the injured. Considerable presence of mind and initiative on the part of members present, no doubt contributed largely to minimising injuries and saving lives.” The men received no honours or awards, because despite the fact they awaiting to emplane to fly into battle, they were not already in battle. The strict censorship at the time of the crash also prevented any honours or awards for the heroic actions of these men.

Sixty infantrymen of the 2/33rd Battalion and two drivers of the 158 General Transport Company lost their lives as a result of the crash. The eleven crew in “Pride of the Cornhuskers” also suffered a terrifying death. A total of 73 men died, with over 90 subjected to horrific burns. It is without doubt, Australia’s worst aviation disaster, yet it remains one of the least documented and known incidents of the Second World War.